Assessment of Clinical Care, and Local Government Opportunities

At the Request of Commissioner Michael F. Hogan

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD*

Edith Kealey, MA, MSW

Patrick Runnels, MD

October 2007

*I am very thankful to my colleagues Ms. Kealey and Dr. Runnels for their important work in thinking through and writing this report. The final report, however, represents the views of this author.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Clinical Care

- Workforce Recruitment and Retention

- Research

- Local Government Opportunities

- Final Thoughts

- Summary of Recommendations

- Reference and Reading Material

- Appendices

Imagine you are ill with a mental illness or have a loved one with a mental illness. What would create confidence in caregivers and services? What would kindle and sustain hope for a life of contribution in your community for yourself or your loved one?

Two masons were cutting stone for a church when a traveler asked each what he was doing. One said "I am killing myself cutting this stone day after day". The other said "I am building a place for people to find peace". Each one of us in our respective professional or governmental communities has the choice of being one or the other of these masons.

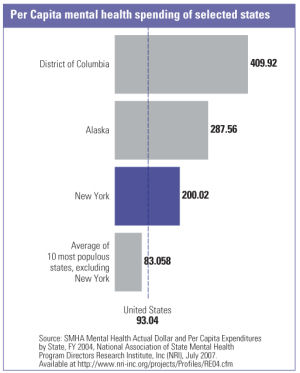

New York ranks third in the nation in per capita expenditures and second in overall expenditures on mental health care, yet by no means can it claim that recipients receive the best services. While adequate financing is necessary, money itself cannot be the determining factor in the provision of quality services. With this in mind, we must ask ourselves: What would it take to make New York State (NYS) a place where people with mental health disorders receive clinical services that meet their needs to live, learn and work in their communities? What would it take to translate the remarkable research of our academic colleagues into everyday practice? What would it take to amplify our remarkable training capabilities and create an ongoing source of dedicated public sector professionals? And, importantly, what would it take to demonstrate that money is being well spent because it produces the results that recipients and their families want?

This report was prepared at the request of Commissioner Mike Hogan who early in his administration decided not to take the tack of ready, fire, aim in response to the urgency we all feel to improve upon the services Office of Mental Health (OMH) directly runs, licenses or funds. Instead, he opted to take stock of what we have, together with our constituent communities, in order to articulate where OMH and the NYS mental health community needs to be and how to best get there, otherwise known as ready, aim, fire. We approached our task with a set of values: we want OMH and its related agencies and programs to be transparent in their actions, to have the recipient first in mind ("person-centered services"), to relentlessly pursue excellence and collaboration, to appreciate individual differences and reduce disparities in care, and to prudently and optimally use public funds. These values informed our visits and shape this report.

We are at a propitious moment. With a new Governor and agency leaders we have an uncommon opportunity to transform NYS mental health services into quality care that is accountable to clients and families, built on commitments to recovery and partnership with constituents, that honors the public trust and meets our fiscal responsibilities, and that allows all stakeholders to feel proud of doing the right thing.

The Organization of this Report

The work that underlies this report was undertaken in response to Commissioner Hogan�s request for an assessment of mental health care in NYS that focused on four major areas: clinical quality, workforce, science to practice, and working with local government units. His assignment is outlined in a memo dated May 10, 2007 (Appendix A). Of course, simultaneous to this work, many other visits, meetings and evaluative efforts, by the Commissioner and the OMH leadership team, have taken place. Thus, this report should be seen as but one component of the early assessment and directional thinking of the agency.

We are also aware that the NYS mental health system has tens of thousands of dedicated and talented clinicians, advocates, and administrators. We do not subscribe to the view that OMH policy directives will produce the changes needed. Rather, we seek to foster a mental health system that benefits from the leadership of people at all levels, guided by a shared vision of recovery-focused, person- and family-centered care.

In carrying out this assessment, we conducted visits and meetings with a broad sample of programs and organizations, both within and outside the boundaries of OMH. Our aim was to provide the Commissioner with a set of recommendations to guide clinical care, recruitment and retention, and research in the years to come, as well as thoughts about how to go about achieving these recommendations. (See Appendix B for a list of the 30 visits undertaken). The report�s recommendations are more at the macro than the micro level in order to achieve a directional tone; some important detail that was gathered appears in the appendices, as does other related material.

While the sample of programs and organizations visited was limited, and we would have liked to meet with even more colleagues, we were able to engage a broad range of constituents, facilities and programs. Especially notable was the remarkable consistency of the themes that emerged in terms of needs, challenges and opportunities. Finally, by design, the recommendations proposed here represent only a fraction of what could be offered; in setting off on this mission, the Commissioner indicated that needed focus would best be achieved by fewer recommendations than by more. Finally, even though the recommendations are limited in number, and some reflect work already underway, the aims expressed here are substantial � thereby calling for prioritization, staging and perhaps most importantly ongoing and effective collaboration with stakeholders and local governments.

Quality of clinical care is both the bedrock and the guiding star for what we owe to people who receive care from mental health service providers. Donabedian, one of the world�s early and great leaders in quality improvement, was instrumental in creating a typology of quality, from structure (how services are organized, staffed and resourced) to process (what is provided to someone) to outcome (what are the results).

Over the past two decades the science of quality assessment has grown substantially and the accent has shifted from assessing structure to measuring, reporting and improving processes and outcomes of care. An even more important development in mental health during this period has been the growth of the consumer voice (client and family) in influencing processes and outcomes of care. In particular, consumers are insisting on a recovery orientation based on hope and dignity that requires a partnership between provider and consumer. The goal of this partnership is for the focus of care to shift away from simply managing symptoms and toward recipients achieving, to the best of their abilities, lives of contribution and self-respect while living in and being a part of their communities.

In meeting with programs and professionals throughout NYS, we were struck by the many examples of outstanding clinical work and quality improvement underway. Furthermore, we were heartened to witness the calibre of so many dedicated professionals eager for the opportunity to build on their good work and be a part of a mission to incorporate and disseminate quality practices and standards throughout the state. At the same time, we were also struck by how rarely there was interchange between programs and local government agencies and how variations in available services so often seemed unrelated to individuals� needs. Transparency, uniform opportunity for services among individuals in need, and dissemination of the work going on need improvement. Such systemic disconnects frequently result in highly isolated or unrecognized efforts, which leave us all subject to public misperception that services offer little of value to recipients. Additionally, we saw how Quality Councils were making a difference at a number of OMH facilities, but believe even more could be accomplished by better engaging consumers and collaborating with sister psychiatric centers in providing, reporting and improving upon clinical care.

Recommendation I A1

Promote openness and transparency in measuring, reporting and improving clinical care.

Examples:

- Establish and implement uniform quality measures for mental health services throughout NYS

- Publicly report on provider and local system performance

- Develop payment methods that support and encourage quality and efficiency, as opposed to simply the production of units of service

Recommendation IA2

Ensure that consumers and families have a central voice and role in quality assessment and improvement activities.

New York State is remarkable for the diversity of its population. Services that will succeed will be those that recognize and respond to our wonderfully diverse cultures and languages. For many years, OMH has had a standing Multicultural Advisory Committee (MAC). Creedmore Psychiatric Center (PC) has a remarkable inpatient unit specifically for people of Asian ethnicity and race. Hamilton Madison House in New York City has distinguished itself for its work with Asian Americans. While many other programs exist we can do more. Culturally competent care is fundamental to service delivery: unless we speak in the language and with culturally informed values we might as well be talking to the wall. However, a great gap persists between where we are and where we need to be. We need to elevate the role of consumers and families and do so in a culturally and linguistically attuned manner in order to meet the goal of community care in which the whole person can be treated in the context of his or her family, community and culture.

At Rockland Psychiatric Center, we saw an impressive dashboard of quality measures guiding day-to-day improvements in care. In NYC, over 250 community-based mental hygiene agencies are using standardized instruments to measure consumer perceptions of care. Many of these agencies are also employing instruments to detect and improve clinical care for people with dual disorders of mental health and substance abuse. At OMH Psychiatric Centers the work over the past few years done by Drs. Molly Finnerty, Lewis Opler and Mr. Chip Felton has remarkably improved the provision of evidence based psychopharmacology. However, these innovations are cloistered: they need to extend out into the community where most people live and get their care. More universal application and transparency would allow consumers (and payers) to understand how care in one site compares with care in another.

Examples:

- Ensure that consumers and families are members of all quality improvement committees or project teams ("nothing about us - without us")

- Embed consumer perspectives and cultural competence in clinical assessment and client satisfaction instruments

- Employ effective, standardized training programs in quality improvement and evidence based practices for clinical leadership and staff at provider organizations

- Ensure that Consumer and Family Advisory Councils exist at OMH run and licensed facilities and programs, and that they directly engage the program leadership

Recommendation 1A3

Promote a flexible continuum of services to ensure that intensity is matched to need.

Inpatient treatment has become the default acute care intervention because too few responsive community based alternatives exist, especially for adults with mental illness. NYS is terribly lacking in flexibly using a continuum of services for people with mental illnesses. NYS has 75 Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams, and NYC has 43 of those teams; in the City, waiting lists are developing, especially in Manhattan. This is related to a persistent ideology that ACT should be provided for life, notwithstanding what we now know about recovery. And despite the remarkable New York New York III Agreement to build 9,000 units of supportive housing in NYC, there are simply too many people with disabilities in need to be accommodated by these units. The rest of the state also faces great challenges in providing safe and reliable housing outside of hospital settings.

Examples:

- Build crisis services, holding beds, and other community services to prevent unnecessary inpatient care

- Introduce care management in ACT and ICM so that clients receive care when they need it and graduate from intensive services when no longer clinically needed

- Allocate supportive housing units to long-stay PC clients, people who are chronically homeless, and those with patterns of Medicaid expenditures that indicate they are the "poorly over-served"

- Create incentives for existing services to work together more effectively in order to provide well coordinated, client-centered care

Recommendation 1A4

Leverage technology to support quality.

One single innovation that could produce great leaps in safety and quality of hospital based care would be the implementation of an Electronic Medical Record (EMR) with Physician Order Entry (POE) and decision support. Health care, especially mental health care, has yet to adequately travel along the information highway. Again and again, we heard this from clinicians at OMH sites as well as colleagues at the Health and Hospitals Corporation (HHC), the Greater New York Hospital Association (GNYHA), and the Health Association of New York State (HANYS).

Examples:

- Charge the Medical Director, the Chief Information Officer and the Executive Deputy Commissioner with establishing an OMH inpatient EMR, with POE, with timelines and adequate staff and resources

- Collaborate with leaders in the voluntary and HHC hospital sectors as well as the community mental health centers and counties to promote standardization and best practices for an EMR

- Over time, migrate the inpatient EMR to OMH community based services

- Implement web-based, publicly accessible reporting of program accessibility, quality and quality improvement while all the time protecting the confidentiality of service recipients

Recommendation 1A5

Engage in public dialogue about promoting mental health.

Many other professions and organizations capitalize on an open market of ideas. When Common Ground, a not-for-profit housing developer in New York City, held a design competition for its first step housing units at the Andrews Residence on the Bowery in lower Manhattan 180 architectural firms from around the world submitted unit design proposals (at no cost), leading to the selection of four of these for use in this former flop house. Such efforts also help to de-stigmatize mental illness, an ongoing problem for all stakeholders.

Examples:

- Regularly entertain program design competitions or festivals of ideas

- For clinical programs

- For quality improvement

- For the survey and accreditation process

- Regularly hold open forums and community meetings that focus on quality with stakeholders and other state and county agencies

B. OMH Operated Programs

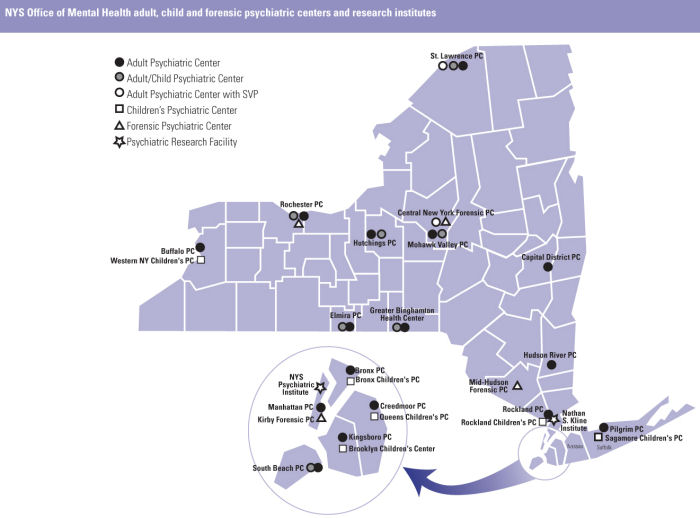

OMH operates 26 psychiatric centers (PCs), including the New York State (NYS) Psychiatric Institute, throughout this state, serving approximately 5,500 adults, children and forensic inpatients as well as many thousands more outpatients. In this assessment, we visited many but far from all of these centers. We saw too much of OMH inpatient care provided at a maintenance level when OMH PCs could be serving as centers integrated with their communities and providing excellent and specialty care. We saw integration in the ways that the Hutchings PC and the Rochester PC worked with their community providers, and were reaching out to even broader localities; we saw how the Western NY Children�s PC is recognized as a hub for child and adolescent service excellence in our western counties; we saw how the child and family service at Saint Lawrence PC is attaining the shortest length of inpatient stays because it has become a part of its community services throughout the expanse of the northern counties.

We have also seen remarkable changes in the OMH child and adolescent services that demonstrate that crisis services and diversion from hospitals and residential centers is possible as is shorter-term, intensive inpatient treatment linked to community care. However, far too many adults in the OMH PCs no longer need hospital level of care and remain for lengthy hospital stays. This results in valuable hospital resources being unavailable for people who are acutely ill and who need intensive care. What�s more, when hospitalized too often an adult consumer�s time is not filled with the kind of clinical interventions or active transitional programs that develop skills and self-assurance while he or she awaits community placement.

Recommendation I B1

Reorient the role of adult state PCs away from long-term care and towards becoming Centers of Excellence in tertiary care.

Examples:

- Develop Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) programs for the cognitive limitations intrinsic to the disease of schizophrenia and for people with trauma disorders; embed these programs into the day to day workings of clinical care units

- Develop more token economies and other positive, reward-based programs, like we see at Buffalo Psychiatric Center, to stimulate functioning in persons with long hospital stays and highly atrophied life skills; embed into them the day to day workings of clinical care units

- Replicate the "Second Chance" program run at Cornell Westchester, the Intermediate Stay Unit at St. Joseph�s in Yonkers, and the South Beach PC program for OMH inpatients with long or repetitive hospital stays

Recommendation I B2

Improve access for people needing inpatient and intensive community care while simultaneously developing more community care options for the OMH inpatients who have reached maximum benefit from inpatient care. Reinvest state resources to meet service needs and enhance community programs, with no reduction in workforce.

Examples:

- Develop a registry of those inpatients who have achieved maximum benefit, by PC, and establish goals and timelines for community placement, on a case by case basis

- Identify and engage for each client community partners who can provide the case management, clinic and rehabilitative services that will enable clients to return to the community

- Track progress with quantitative measures of success

- Allocate a set number of new and re-rental housing to PCs to use for long stay or frequently readmitted patients

- Identify development opportunities for crisis services to actively intervene for brief periods of time, with holding beds if needed, in order to enable consumers and their families to avoid hospitalization entirely

Recommendation I B3

Enhance OMH forensic programming for prison and jail diversion and strengthen re-entry linkages and services; build upon the clinical quality of mental health services within correctional facilities.

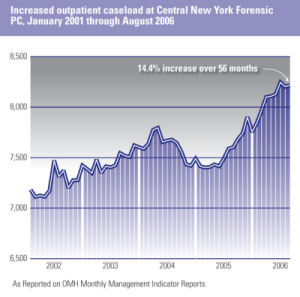

The forensic services division of OMH faces incredible challenges in working to respond to the exponential growth of the number of inmates with mental illnesses in the prison population and in meeting the mandates of NYS sexual offender legislation. Prisons (and jails) have become de facto mental institutions in the wake of deinstitutionalization and the fragmented community care that ensued, amplified by the increased prevalence of substance abuse and the declining beneficial effects of social institutions such as family, neighborhoods and religion. At the same time, awareness of the prevalence of mental disorders among inmates and opportunities to improve care and redirect resources in a cost-effective manner has grown. In fact, not only is clinical quality care essential to improving outcomes and recovery for inmates it is also instrumental to managing the safety and risk of this population. Fundamental strategies for OMH and its partners working with inmates include diversions of individuals with mental illnesses from correctional facilities when appropriate, providing excellent care when people with mental illnesses are incarcerated, and linking individuals to services upon re-entry into their communities.

Examples:

- Promote the development of Behavioral Health Units (BHUs) in state operated prisons

- Foster expansion of mental health (and drug) courts

- Collaborate with correctional and community based programs to improve re-entry services for inmates leaving facilities

Recommendation I B4

Foster professional development and collegial working relations among the clinical leadership and professional staff of the OMH PCs.

In 1844, in the United States, directors (superintendents) of what were then called asylums came together to create a community of clinical leaders that provided and promoted what was called Moral Therapy, a belief in the well ordered hospital where patients were treated with dignity and their time purposefully engaged; it was an enlightened approach to care that believed in hope, recovery and return to the community. These leaders later formed the American Psychiatric Association and founded the journal that today is the American Journal of Psychiatry. Clinical leadership and quality of professional life can be inherent to working in the public mental health care system. The leadership and staff of today�s OMH PCs can become heir to the tradition established in the era of Moral Therapy.

Examples:

- Establish an OMH Office of Professional Recruitment and Retention (see also below in Workforce section) dedicated to enhancing the quality of professional life, skill development and academic productivity of OMH professional staff

- Identify and establish opportunities for professional training, development, mentorship and academic teaching and publication for OMH medical and other professional staff

- Establish and enhance public-academic partnerships between the PCs and local universities, focusing on teaching, training and opportunities for clinical and services research, as well as clinical performance improvement projects

In the early 1960s, a movement began in this country to deinstitutionalize individuals living in the state psychiatric hospitals and build comprehensive, community based services that would enable people with mental disorders to obtain care in their communities and avoid the regressive effects of long-stay hospital care. Sadly, an idea so full of promise and passion (not to mention a good deal of thoughtful services planning) slowly devolved into the fragmented and "broken" community mental health services we see today. A host of factors converged to produce a failed policy � evidenced by the great numbers of people with mental illnesses who are homeless, in shelters, and in jails and prisons. These are people who have searched in vain for high quality, consumer oriented medical and mental services where resources are promptly marshaled and prudently used only if and when they are needed. Those people who suffer from multiple comorbidities, including medical, mental and substance disorders and mental retardation/developmental disabilities, have even greater barriers to proper care. NYS can provide integrated, accountable, community based services for defined populations.

A ward at Hudson River Psychiatric Center prior to deinstitutionalization.

Some of the forces at work that have produced these problems (e.g., the Federal government�s virtual abandonment of low income housing production) are beyond the scope of OMH to remedy. But we must address a core problem that was caused by New York�s approach to mental health � namely its extreme fragmentation of care, with no one responsible for the overall well being and recovery of people with mental illness. In New York, no "top down" or bureaucratic solution to this problem is feasible. Instead, innovative, locally driven solutions hold great promise, such as we see in the children�s "system of care" approach which knits services together to meet individual and family needs and in the Western New York Care Coordination Project which addresses fragmentation with strong, person-centered care planning.

A transformation is underway in mental health services, inscribed in publications such as the President�s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health and by the Institute of Medicine�s Crossing the Quality Chasm and Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. We are seeing a revitalization of the possibilities not realized for over forty years. In New York State new leadership in government and in the consumer and provider community make for the types of alignments needed for transformation, and too many years of missed opportunity have spawned the determination this will take.

Recommendation I C1

Promote county and provider based recovery oriented innovation to serve defined recipient populations or specified geographies across all levels of care.

Examples:

- Promote the work of the Western NY Care Coordination Project (a multi-county care initiative for people with serious and persistent mental illnesses (SPMI), and seek to replicate and extend upon its successes to date

- Promote partnerships between local government units (LGUs), providers and peer run agencies that assume clinical care responsibility organized around clients, not billable services, and who see "love and work" (as Freud said) as the goals of treatment

- Construct novel financing mechanisms to support patient-centered, risk-bearing, performance based community care

Recommendation I C2

Develop collaborations that optimize the care of people with multiple disabilities.

Examples:

- Implement the recommendations of the NYS Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS)-OMH Task Force on Co-occurring Mental and Substance Use Disorders (see Appendix C)

- Develop and implement collaborations that integrate the care of people with co-occurring mental illness and mental retardation/developmental disability; begin with acute and intensive levels of care, where families tell us the need is the greatest

- Promote the development of primary care medical services in mental health settings

- Test various models to determine what works best for whom in different areas of the state

- Seek opportunities to establish one primary case manager for clients under care in multiple agencies, within the same or across different disability areas

Recommendation I C3:

Introduce screening for and care management of high prevalence, high burden and high cost disorders in primary and mental health care, targeting opportunities where current practices do not meet quality standards and which present clear opportunities for improvement.

For those people who are fortunate and can access care, NYS needs to improve upon the quality of the services they receive. Medications are one essential dimension of the treatment received by adults with SPMI and children with serious emotional disorders (SED). In NYS, over 500,000 people annually on Medicaid with a mental health diagnosis or receiving mental health services are prescribed antipsychotic and antidepressant medication. We as yet do not know as yet how many more are prescribed these medications for other diagnoses nor whether doses and duration of medication actually taken is consistent with best practices and effectiveness.

An estimated 400,000 people in NYC suffer from depression each year. For adults with depressive illness served in primary care settings, fewer than one in eight receives what would be regarded as minimally adequate care, a fact that would not be tolerated if the illness were cancer, diabetes or heart disease.

Examples:

- Implement quality improvement interventions for Medicaid recipients receiving psychiatric medications in ambulatory mental health and general medical settings

- Build on the national expert quality improvement work underway between OMH and the NYS Psychiatric Institute and the Columbia University Department of Psychiatry

- Collaborate with the Office of Health Insurance Programs at the NYS Department of Health (OHIP) on their initiatives, including childhood Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder in primary care

- Develop the work begun at the NYC Department of Health Division of Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) on adult depression detection and management in primary care; seek grant support to promote spread

Recommendation I C4:

Develop affordable housing and other community based development initiatives to complement existing supportive housing for people with mental disorders throughout the state.

No one recovers from a mental (or substance use) disorder unless he or she is safely and reliably housed. Truly remarkable development has been achieved with supportive housing throughout NYS, especially in NYC through its landmark City-State agreements, including the most recent 9,000 unit NYNY III Agreement. But if you do the numbers � considering PC inpatients, the chronically and street homeless, high users of Medicaid mental health inpatient services, people languishing in adult homes that are a blight on our care system, not to mention those early in their illness where housing will play a pivotal role in their wellbeing � it is clear there will never be enough supportive housing units for those in need. This need for housing for people with mental disorders was one of the most common themes we heard from a very broad base of constituents.

In 1963, in France, the first L�Arche (literally The Arc) community was established that placed people with mental disabilities in a home with "assistants" or people who co-habitate the homes. These communities have since spread internationally and today number over 100 communities in 26 countries, demonstrating that those who are most ill can lead normal lives in their communities, large and small, when they are given the opportunity. In Gheel, Belgium, for over 600 years, a small city has served as a community for people with mental disabilities from near and far where people with mental illnesses and developmental disabilities live with families and are simply a part of everyday community life.

Examples:

- Collaborate with the Housing Finance Administration (NYS HFA) and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (NYC HPD) and other key state and city agencies to allocate a meaningful % of new housing stock to people with mental disorders; link these units to community based services

- Pursue collaborations with innovative organizations doing community development to reduce illness burden and homelessness in high need neighborhoods

- Use OMH facility real estate for housing development, especially for those who are hardest to place

- Pursue opportunities to sponsor innovative community living alternatives, such as L�Arche and Gheel, that build on normalcy and community integration for those with mental disabilities

Recommendation I C5

Increase capacity for child and adolescent services.

Perhaps no other area of mental health suffers from inadequate capacity as does child and adolescent services. We have been told throughout our assessment that it now takes an act of providence to get a clinic appointment for a child or adolescent and a miracle to see a child psychiatrist.

Examples:

- Build on the work of Child and Family Clinic Plus and further increase Clinic Plus and other child clinic services capacity using a variety of payment and other incentives

- Expand child waiver slots

- Build on existing efforts to integrate and coordinate child services

- Expand telepsychiatry services, especially for rural counties

- In conjunction with the CLMHD, the Schuyler Center, and local branches of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians develop a strategic plan to support the provision of evidence based mental health practices for children and adolescents in primary care

- Increase the supply of psychiatric nurse practioners and physician assistants

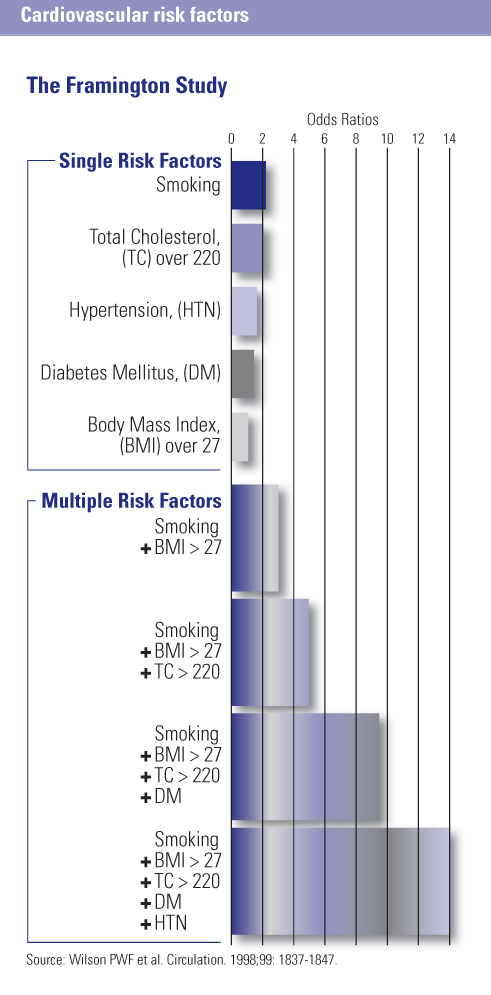

Former Surgeon General Dr. David Satcher came to say that " …there is no health without mental health." Interestingly, in recent years the mirror image of this wisdom, namely that there is no mental health without health, has become disturbingly clear as evidence has emerged that people with SPMI who are cared for in the public mental health system are dying on the average 25 years before their peers. This premature mortality is attributable almost entirely to chronic medical illnesses such as cardiovascular and lung disease and diabetes, not principally from suicide. A priority for OMH will be to integrate health and mental health, in OMH run services and in the community.

South Beach Psychiatric Center (SBPC) understood this problem over ten years ago. Despite many false and failed starts with different partners, SBPC persisted and has created a partnership with Maimonides Medical Center for three primary care clinics co-located at three SBPC outpatient clinics in Brooklyn. Today, almost 300 people with SPMI walk in the same front door to receive care for their medical and mental disorders; peer consumers will soon be serving as wellness coaches in these clinics; and internists and psychiatrists confer regularly on their patients and, with proper consent, have access to medical information to ensure that health and mental health care are inextricably linked � just as they are in the person being served. Among the licensed community based mental health organizations, a group of leadership agencies in the NYC area, namely ICL, The Bridge and FEGS, in conjunction with the Urban Institute for Behavioral Health (UIBH), have come together to work on how best to reduce physical illness and death among people with chronic mental illness. Their approach also incorporates improving the identification and management of medical illnesses at mental health sites of service. They recognize that the principal place where people with chronic mental disorders seek services (their "medical home") is not in the primary care doctor�s office, but in the mental health clinic or program where they go for services.

Recommendation I D1

Support programs that provide medical care to consumers in mental health care settings.

Examples:

- Support partnerships among mental health, primary care, visiting nurse and hospital systems; fund pilot programs to determine what works best for whom and when

- Consider developing medical disease registries among people in the public mental health care system

- Develop expert consensus standards and best practices for the medical care of people with mentally illness

Recommendation I D2

Prioritize consumer and provider wellness initiatives, focused on smoking cessation, prevention, activity and nutrition (SPAN).

Yet, as the informed reader will have already said to him/herself, isn�t it kind of late to intervene when the disease is already active and doing harm? Does it not also neglect the process of consumer self-care?Wellness and prevention efforts, in full partnership with consumers, are needed to enable our clients to take more control over their health and well being.

Examples:

- Implement SPAN programs at all OMH PCs

- Establish, monitor and improve measures of cardiometabolic risk factors in OMH consumers

- Support community mental health provider wellness initiatives

Recommendation I D3

Identify and promote opportunities to engage primary care providers around interventions for high prevalence, high burden mental disorders.

We have long known that most people with highly common mental disorders, such as mood and anxiety disorders (including depression and post-traumatic disorders), do not and will not go to specialty mental health settings for their care. This is especially true at both poles of the age continuum, children and seniors, and among immigrants and minorities. To reach these people whose disorders go frighteningly under-detected and under-treated, when so much can be done, we must build screening and evidence based care into the standard operations of primary care and educational settings, where most people access care and which carry less stigma.

Examples:

- Propagate depression detection and care management in primary care for adults, already substantially underway in NYC with screening and management tools and a spread strategy that is focused on large scale practices such as public general hospitals, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), senior centers, and colleges and universities

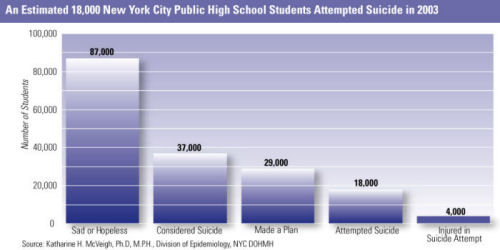

- Since rates of depression in NYC public high schools have been detected by the Youth Risk Behavioral Scale (YRBS) to be as high as one in three students, launch a public mental health initiative whose goal is depression screening for adolescents in pediatric and family practices offices and in public and private high schools

An Estimated 18,000 New York City Public High School Students� Attempted Suicide in 2003�

Section II Workforce Recruitment and Retention

There was nowhere that we went, nor virtually any meeting we attended on this project, that we did not hear about the workforce crisis in mental health. A survey done by the Conference of Local Mental Hygiene Directors (CLMHD) identified that 23 of the 57 counties in NYS (not including NYC) have no child psychiatrist (See Appendix D). Waiting lists abound to see a psychiatrist throughout the state, and public mental health providers recruit endlessly to bring on capable doctors to their clinics. Nursing shortages are rife and social workers are often recruited away by pharmacies and care management organizations. The crisis in professional recruitment and retention now threatens access and quality of care throughout OMH and community mental health agencies.

Child psychiatric training programs have reduced in numbers since the 1980s, while grey-haired child psychiatrists retire faster than they are replaced. Payment for child and adolescent services under Medicaid barely covers the expense of the office and the children�s toys scattered about the waiting room while trainees graduate with more debt than ever, typically exceeding $100,000. Psychiatric residency programs concentrate in urban areas, as do fellowships in child/adolescent psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry and forensic psychiatry, leaving rural sections of NYS particularly bereft.

We recognize the vital role that paraprofessional staff provides throughout OMH and community based services. There are many areas for improvement for this workforce which need and warrant attention. However, we confine our comments to the clinical professional workforce, which is the focus of this report.

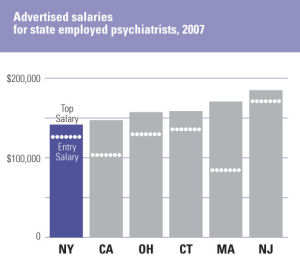

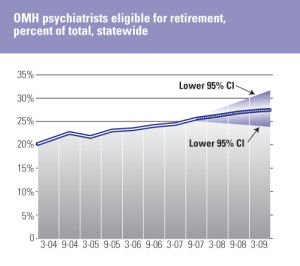

To inform this report, the OMH Office of Psychiatric Services and Research Institute Support undertook an analysis of psychiatrist salaries in NYS and compared these to neighboring and other large states. Appendix E provides detail on comparative marketplace salaries as well as illustrates that 20-30% of the OMH psychiatrist workforce will be eligible for retirement within two years. OMH salaries have not kept pace with the market and deter some psychiatrists from even applying for a job at OMH. While we have not done an analysis of nursing salaries, we heard repeatedly during our visits how licensed nurses were paid substantively higher in general hospital and nursing home settings. The result is growing vacancies and an increasing need for what is called "mandation" (the requirement that a nurse remain for a second shift because the staffing would not be sufficient and safe were s/he to leave the hospital). How can we recruit and retain nurses if salaries are not competitive and we require them to stay beyond their shift, with virtually no notice, instead of returning home to their children and families?

Recommendation II 1

Establish an OMH Office of Professional Recruitment and Retention.

Functions:

- Develop and implement a multi-year strategy to increase the numbers of adult, child, forensic psychiatrists, primary care physicians, and licensed and advanced practice psychiatric nurses working in public mental health care settings

- Collaborate with the CLMHD and the Schuyler Center in their STEPS campaign to improve access to child and adolescent psychiatrists and primary care and psychiatric nursing professionals providing psychiatric services

- Identify and implement recruitment and retention incentives, such as loan forgiveness, mentoring, education, and teaching and research opportunities; link to budget proposals

- Identify and implement non-wage compensation enhancements, including housing, professional education, and performance based rewards for clinical excellence

- Advocate for marketplace and geographic adjustments in psychiatric and nursing salaries; link to budget proposals

- Assist international medical and nursing professionals in achieving full NYS licensure

- Improve physician and nursing professional development and training opportunities at OMH facilities

- Collaborate with OMH affiliated academic and training programs to provide training, consultation and research activities at OMH facilities

Recommendation II 2

Promote early and lifetime public psychiatry training and consultation.

Early contact with future physicians and ongoing professional education for career professionals will be essential to meeting staffing needs in the years to come. Psychiatric educators know that it takes reaching the hearts and minds of young medical trainees, in medical school and residency, if they are going to choose psychiatry as a career. We can generate excitement in future physicians by making them welcome on public psychiatry services, actively engaging them in patient care, and showing them the remarkable science and art that is our profession. We will also retain talented staff by enriching their professional life with ongoing education, access to experts and mentors, and by ensuring contact with consumers and families who have benefited from effective care.

Examples:

- Expose and train medical students and psychiatric residents in public psychiatry and principles of recovery vCollaborate with OMH affiliated academic programs to provide clinical training, consultation, and research activities in OMH PCs and in community based public mental health settings

- Increase the provision of OMH conferences, Grand Rounds, and telepsychiatry training events

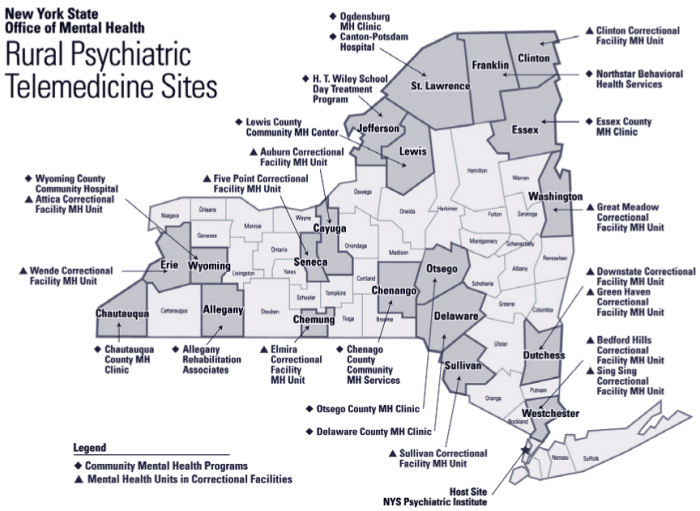

- Extend telepsychiatry consultation to all rural county mental health settings and to primary care providers

- Conduct a review of the 25 existing academic training and affiliation agreements and recontract for July 1, 2008 to improve long term recruitment and retention of psychiatrists

Recommendation II 3

Assess OMH�s current agreements with its academic affiliates to determine and improve upon the public psychiatry training of residents and the ongoing education of OMH professional staff.

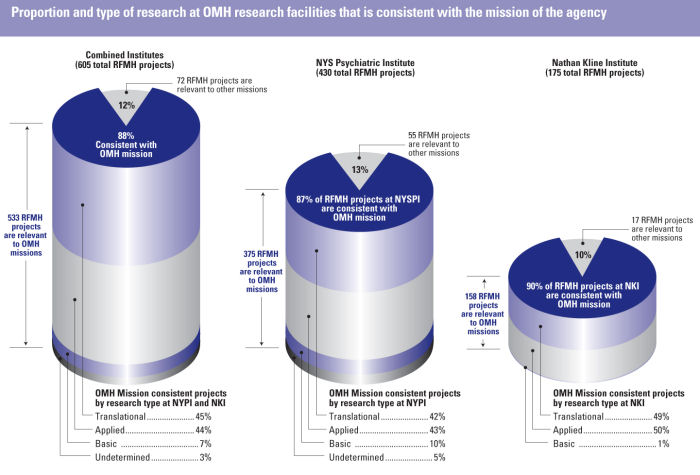

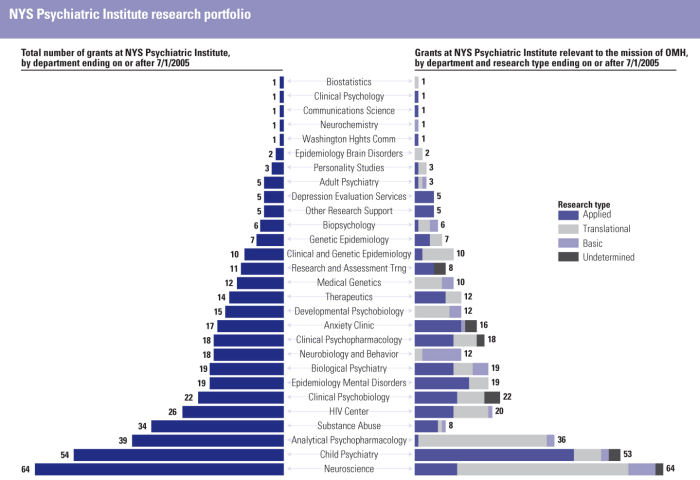

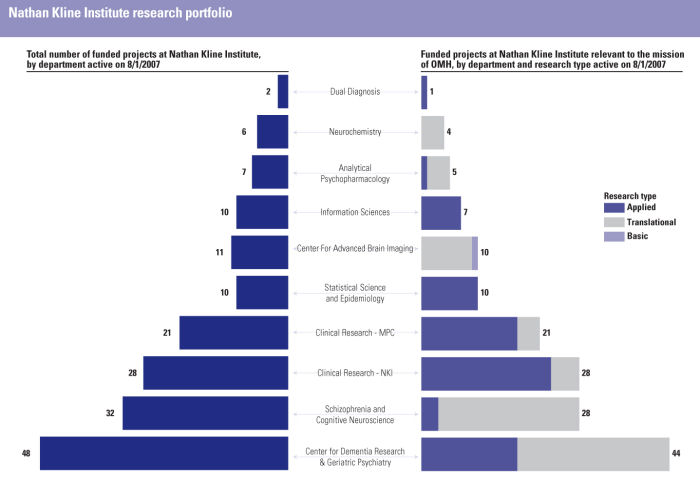

While many talk of public-academic partnerships, OMH has the truly remarkable benefit of having two research institutes that are part of the fabric of our agency. New York State Psychiatric Institute (PI), affiliated with Columbia University, and Nathan Kline Institute (NKI), affiliated with New York University, are directed by Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, and Harold Koplewicz, MD, respectively, and position OMH to have science inform practice � through basic, translational and applied research � and to have the greatest challenges of practice inspire the science conducted.

This report has focused on the work of PI and NKI but it would be a great omission not to recognize the important and exciting work underway by two services research and evidence-based practice (EBP) bureaus within OMH. Dr. Molly Finnerty heads the adult bureau in the OMH CITER Division, under the leadership of Chip Felton, MSW, and Sheila Donahue, and Dr. Kimberly Hoagwood heads the child and family bureau at PI. Their bureaus are models of research enterprises that emphasize how to implement and sustain EBPs, bring science to practice, and ensure that pressing treatment issues inform the OMH research agenda.

As a component of this report, we asked each institute to inventory its portfolio of research and categorize existing grants according to their alignment with the OMH mission. Appendix F depicts the work underway at each institute funded via the Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, according to whether it falls within the OMH mission, and, for mission-relevant studies, whether the research is basic, translational or applied. We are thankful to Susan Essock, PhD, Director of the Department of Services and Policy Research at PI, for helping to conceptualize the sorting algorithm we present. At the time of this report, we are further examining this material to better understand the potential of the applied research and its congruence with the OMH mission.

Our goal is to see further growth of mission-relevant applied research on topics of the highest priority to OMH while sustaining the existing deep commitment by PI and NKI to basic and translational research that will foster the discovery and innovation needed to advance knowledge and improve the lives of consumers and their families. Effective clinical interventions exist today because of the successful basic and translational research whose shoulders we stand upon. Tomorrow�s advances depend on today�s efforts in experimental therapeutics and in understanding the causes of mental disorders.

In a research portfolio, as in a financial investment portfolio, diversified holdings enable short and long term benefits, enhance the likelihood of progress on multiple fronts, and require that that all eggs are not in one basket. Applied research aims to produce knowledge that is more immediately relevant and applicable to clinical care; translational research aims to illuminate where discovery can enter the realm of practice; and basic research aims to identify underlying genetic, environmental, neuroanatomic, neurochemical and physiologic mechanisms as well as etiologic and pathogenic processes that will point the way to the future of prevention and therapeutics. Each part of the portfolio is complementary to the other, and tends to yield its contributions at different times. For the purposes of this report, the Institutes categorized projects that investigate normative brain or behavioral functioning in humans or animals as basic research. Projects that investigate a disorder (and may involve research with humans or animal models of a psychiatric disorder) were categorized as translational. Projects involving clinical care (including interventions, services and diagnosis) with people with mental illness fall into the applied category.

Recommendation III 1

Inventory the research portfolios of PI and NKI, with a particular focus on applied research, and develop with the institute directors a multi-year strategy for enhancing OMH mission and policy relevant research.

Examples:

- Pursue opportunities to increase grant funding and the number of research scientists working in the area of applied services research, for example:

- Improving our knowledge of program and population based interventions (i.e., what works for whom?)

- Improving our knowledge of clinical performance processes and outcomes (i.e., was the intervention actually received by the service recipient and with what results?)

- Improving our knowledge of ways to organize and finance care to promote optimal outcomes (i.e., are payment incentives aligned to serve recipients?)

- Further develop research on consumer decision making, engagement and participation in recovery-oriented care

- Promote recovery oriented services through research to change provider behavior

- Use epidemiological and intervention scientific expertise to shape statewide planning (The 5.07 Plan), in conjunction with the counties

- Pursue opportunities to increase grant funding and research scientists working to accelerate translation of basic biomedical discoveries into new diagnostic and therapeutic tools

- Pursue new applications of genetics and brain imaging to advance the science of "personalized medicine" to:

- Identify disease risk before illness occurs

- Increase diagnostic precision

- Improve selection of medication to optimize response and minimize side effects

Recommendation III 2

Develop greater public and governmental awareness of the work underway at the OMH research institutes.

Examples:

- Hold an annual Albany research demonstration day for elected officials and governmental senior staff that shows the value and promise of the Institutes� activities

- Develop and implement a strategy for joint research projects with counties and community providers to discover how best to implement and sustain appropriate, accessible and high quality services

- Develop public awareness campaigns on promising research developments in psychiatry and public mental health

Recommendation III 3

Collaborate with PI and NKI on projects to improve the public mental health of New York State residents.

Examples:

- Examine Medicaid data on prescribing practices for people with mental disorders and develop and implement quality improvement interventions that improve client outcomes in cost-effective ways

- Evaluate the impact of New York New York III � 9,000 units of supportive housing for residents of NYC � to assess its effectiveness in improving client lives and thereby reducing the use of health, mental health, correctional and social welfare services

Section IV Local Government Opportunities/p>

NYS has 57 counties plus NYC, where each borough is a county. A county is also referred to as a local government unit (LGU) and has a Director of Community Services (DCS) who oversees the LGU mental health (and generally mental retardation and chemical dependency) services. OMH funds a significant portion of LGU mental health services through local assistance; this does not include Medicaid, the largest payer of public mental health services. NYC purchases services from not-for-profit community based mental health organizations and generally runs no services, while other counties for the most part are both service providers and purchasers. The counties are collectively represented by the Conference of Local Mental Hygiene Directors (CLMHD).

As a former DCS for NYC, I had the experience of seeing how disconnected OMH had become from the counties. While planning, funding, licensing, and regulatory decisions are concentrated at the state level, the counties are charged with providing local services according to population needs and knowledge of evidence based treatments, able providers, and available resources. Effective collaboration between OMH and county agencies is one of the best opportunities we have to improve services for consumers and their families.

Recommendation IV 1

Engage counties in developing the NYS 5.07 Plan � the annual statewide planning mandate � and promote flexible use of funds.

Examples:

- Adopt a template for local planning developed with the CLMHD that draws upon epidemiological data and establishes local priorities to complement state planning goals

- Jointly publish county and state plans and pursue collaborative implementation between LGUs and OMH Regional Offices

- Develop technical assistance capacity provided by OMH to smaller counties to use in the development of future local plans

Recommendation IV 2

Simplify categories of local aid and promote flexible use of funds. Rationally allocate high intensity and high cost services.

Counties are too constrained in the innovation and management of services they purchase and provide. Currently there are over 50 categories of state aid that flow to the counties. LGUs can only spend these allocations in their respective categories, which often reflect bygone eras of service provision and do not allow for local innovation. Moreover, little or no management of services and service dollars occurs, beyond assuring that contractual and regulatory obligations are met. As a consequence, too often there is no "off ramp." Clients begin services, like ACT, ICM, Community Residences, supportive housing and other scarce and costly resources, and never move on, even when they are clinically able to do so.

Examples:

- Collapse state aid into as few categories as meaningfully and legally permissible, and consistent with Medicaid regulations

- Link flexible funding to State and County 5.07 Plan priorities

- Authorize Single Point of Accountability (SPOA) and other care management organizations to provide utilization management for high intensity services and high cost consumers

- Support county-provider risk-based partnerships for mental health and medical care for defined groups of consumers

- Build on the innovative work of the Western NY Care Coordination Project

Recommendation IV 3

Identify and implement NYC specific initiatives in partnership with the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

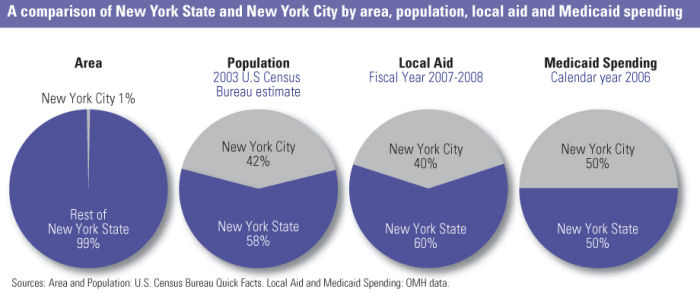

New York City represents almost half the population of the state, 40% of the local aid distributed, and an even greater percent of Medicaid spending. The scale and concentration of people and services makes the City unique. The central role of the Division of Mental Hygiene (DMH) in the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) in the City�s planning and service provision, and its strong analytic and policy capabilities, offers an important opportunity for partnership with OMH.

Examples:

- Collaborate on public mental health population based initiatives such as:

- Depression screening and management

- Consumer wellness programs

- Improve the performance of both the case management and housing SPOA and rationally manage high intensity and high cost services

- Promote primary health care in mental health settings in conjunction with the Coalition of Voluntary Mental Health Agencies and the Urban Institute for Behavioral Health

A comparison of New York State and New York City by area, population, local aid and Medicaid spending Area� Population� Local Aid� Medicaid Spending� 2003 U.S Census� Fiscal Year 2007-2008� Calendar year 2006� Bureau estimate New York City 1%�

I would like to thank all those who generously gave their time and thoughtfulness to us as we visited programs and constituents around the state. It was a remarkable experience and a privilege to see so many dedicated people working to meet the needs of people with mental illnesses and their families.

Yet we were left with the feeling that too much is going undone in a state so full of talent and resources. Imagine the possibilities were we to better use the advances in service delivery that have emerged, particularly in the past ten years. These advances pertain more to community living, recovery and rehabilitation than to pharmacological advances, which unfortunately still await new breakthroughs. While medications can effectively treat symptoms � no small achievement � improving functioning and course of illness remain goals for genetic and biological researchers to pursue, especially for the chronic mental disorders that are core to the mission of OMH. However, we now have better psychosocial interventions, opportunities to share in decision making with consumers and thus improve engagement in treatment, and we can far more responsibly use the great human and capital resources of New York State. Imagine a care system that is highly transparent, consumer and recovery focused, effective and cost-effective, and is reducing the shameful disparities that haunt healthcare.

The view that mental disorders fate people to lives of disability is false and outdated. People can and do recover and build lives of hope and contribution in their communities.

Enabling recovery is our collective calling.

Section VI Summary of Recommendations

I. Clinical Care

A. Quality of Care

| Recommendation I A1 | Promote openness and transparency in measuring, reporting and improving clinical care. |

| Recommendation I A2 | Ensure that consumers and families have a central voice and role in quality assessment and improvement activities. |

| Recommendation 1A3 | �Promote a flexible continuum of services to ensure that intensity is matched to need. |

| Recommendation 1A4 | �Leverage technology to support quality. |

| Recommendation 1A5 | Engage in public dialogue about promoting mental health. |

B. OMH Operated Programs

| Recommendation I B1 | �Reorient the role of adult state PCs away from long-term care and towards becoming Centers of Excellence in tertiary care. |

| Recommendation I B2 | �Improve access for people needing inpatient and intensive community care while simultaneously developing more community care options for the OMH inpatients who have reached maximum benefit from inpatient care. Reinvest state resources to meet service needs and enhance community programs, with no reduction in workforce. |

| Recommendation I B3 | �Enhance OMH forensic programming for prison and jail diversion and strengthen re-entry

linkages and services; build upon the clinical quality of mental health services within correctional facilities. |

| Recommendation I B4 | �Foster professional development and collegial working relations among the clinical leadership and professional staff of the OMH PCs. |

C. Community Based Programs

| Recommendation I C1 | �Promote county and provider based recovery oriented innovation to serve defined recipient populations or specified geographies across all levels of care. |

| Recommendation I C2 | �Develop collaborations that optimize the care of people with multiple disabilities |

| Recommendation I C3 | �Introduce screening for and care management of high prevalence, high burden and high cost disorders in primary and mental health care, targeting opportunities where current practices do not meet quality standards and which present clear opportunities for improvement. |

| Recommendation I C4 | �Develop affordable housing and other community based development initiatives to complement existing supportive housing for people with mental disorders throughout the state. |

| Recommendation I C5: | Increase capacity for child and adolescent services. |

D. Health And Mental Health

| Recommendation I D1 | �Support programs that provide medical care to consumers in mental health care settings. |

| Recommendation I D2 | �Prioritize consumer and provider wellness initiatives, focused on smoking cessation, prevention, activity and nutrition (SPAN). |

| Recommendation I D3 | �Identify and promote opportunities to engage primary care providers around interventions for high prevalence, high burden mental disorders. |

II. Workforce Recruitment And Retention

| Recommendation II 1 | Establish an OMH Office of Professional Recruitment and Retention. |

| Recommendation II 2 | Promote early and lifetime public psychiatry training and consultation. |

| Recommendation II 3 | Assess OMH�s current contracts with its academic affiliates to determine and improve upon the public psychiatry training of residents and the ongoing education of OMH professional staff. |

III. Research

| Recommendation III 1 | Inventory the research portfolios of PI and NKI, with a particular focus on applied research, and develop with the institute directors a multi-year strategy for enhancing OMH mission and policy relevant research. |

| Recommendation III 2 | Develop greater public and governmental awareness of the work underway at the OMH research institutes. |

| Recommendation III 3 | Collaborate with PI and NKI on projects to improve the public mental health of New York State residents. |

IV. Working With The Counties, Including NYC

| Recommendation IV 1 | Engage counties in developing the NYS 5.07 Plan - the annual statewide planning mandate - and promote flexible use of funds. |

| Recommendation IV 2 | Simplify categories of local aid and promote flexible use of funds. Rationally allocate high intensity and high cost services. |

| Recommendation IV 3 | Identify and implement NYC specific initiatives in partnership with the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. |

Section VII Reference and Reading Material

American Psychiatric Association: Report of the APA Task Force on Quality Indicators and Report of the APA Task Force on Quality Indicators for Children, APPI, 2002, Washington, DC

City Health Information (CHI): Detecting and Treating Depression in Adults, NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Vol 25 (1): 1-8, January 2006

Donabedian, A: Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Quarterly 1966; 44:166-203

Frank, RG, Glied, SA: Better But Not Well: Mental Health Policy in the United States since 1950, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006, Baltimore, Maryland

Health Policy Institute: Changing the Landscape: Depression Screening and Management in Primary Care, Washington, DC, 2005

Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press, 2001, Washington, DC

Institute of Medicine: Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions, National Academies Press, 2006, Washington, DC

Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity, A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001, Rockville, Maryland

Miller, WR, Rollnick, S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd Edition, The Guildford Press, 2002, New York, NY

Osborne, D, Hutchinson, P: The Price of Government: Getting the Results We Need in an Age of Permanent Fiscal Crisis, 2004, Basic Books, New York, NY

Parks, J, Svendsen, D, Singer, P, Foti, ME: Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD), Medical Directors Council, 2006, Alexandria, Virginia

The President�s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health in America, Final Report, US Department of Health and Human Services Pub. No. SMA-03-3832, 2003, Rockville, Maryland

Rush, J, First, MB, Blacker, D: Handbook of Psychiatric Measures, Second Edition, APPI Press, 2007, Washington, DC

Sederer, LI: Moral Therapy and the Problem of Morale, American Journal of Psychiatry, 134:3; 267-272, 1977 vSederer, LI, Dickey, B: Outcomes assessment in clinical practice. Williams and Wilkins, 1996, Baltimore, MD

United Hospital Fund - Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, Center for Health and Public Service Re search: High Cost Medicaid Patients: An Analysis of New York City Medicaid High Cost Patients, March 2004

Appendix A Assignment Memo

| To | Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, Medical Director |

| From | Michael F. Hogan, PhD, Commissioner |

| Date | May 10, 2007 |

| RE | Assessing Clinical Quality in New York�s Mental Health System |

Congratulations on your appointment as OMH Medical Director. You will provide leadership for New York�s clinical care system of hospitals and community services.

To assess our status and focus our efforts, you will review critical issues in clinical quality across New York. Clearly this is a major task and will require a balance with your significant operational responsibilities. While the major product will be a written report with recommendations for action, I believe the process of your review will be important as well in building consensus among our diverse shareholders�who have not always been consulted on OMH priorities. The assessment will involve conversations with leaders�from consumer and family advocates to clinicians and managers across New York; obviously only a sample of programs can be visited.

I would suggest the areas of review could include the issues listed below. However, I also believe it may be appropriate for you to adjust the agenda as you proceed.

- Clinical Care

- Hospitals and Community-based OMH Services

- Psychiatric services

- Clinical care, including safety, appropriateness of care (including EPBs), outcomes, and consumer and family perceptions of care

- Professional recruitment and retention, especially for psychiatrists (including specialties) but including other professional health personnel.

- Training, including residents and other clinical trainees.

- Academic activities that support patient care, including teaching and publishing

- Medical services

- Medical care for inpatients

- Community based wellness and self-care; screening as well as secondary and tertiary prevention for medical disorders; and linkages to community-based primary care services

- Provision of medical services co-located at OMH inpatient and community facilities (primary care with expertise and interest in people with SPMI and SED children)

- Quality Assurance, Quality Improvement and Performance Measurement

- Quality Assurance and Performance Measurement, including defined clinical performance measures for hospitals and community services.�

- Use of Quality/Performance Improvement, including rapid cycle (PDCA) unit based, multidisciplinary projects.

- Psychiatric services

- Psychiatric Services in the public sector: the adequacy of psychiatric services in community settings, including Article 31 and 28 Clinics, Hospitals, Residential settings and Rehabilitation programs for adults and children. Because OMH does not have direct managerial authority over these settings other means of influence will apply, including licensing, payment, performance measurement, contracting, and professional affiliations and standards.

- Recruitment and retention and clinical access to adult, child and forensic psychiatrists

- Role of psychiatric training programs in public psychiatry

- Role and responsibility of psychiatrists

- Wellness and self-care programs

- Linkages to primary care

- Effective use of high intensity services such as Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) and ICM, AOT, and supportive housing AssignmentMemo An Assessment of Clinical Care, Professional Workforce, Research and Local Government Opportunities

- Hospitals and Community-based OMH Services

- Relationship between NYC OMH Field Office and NYC DOHMH Division of Mental Hygiene

- Explore/define synergies for service planning, purchasing and quality monitoring between the City and the State.

- Considerable opportunities exist for public mental hygiene initiatives between City and State, such as depression in primary care, wellness and self-management, and effective linkages between mental health and primary care focused on high prevalence, high risk chronic medical diseases

- Clinical Research

- Research with immediate relevance and application. Assess the focus and productivity of research to inform practice

- Epidemiology

- Trends in incidence and prevalence of mental disorders, disease burden, service need and utilization, and system capacity in the service of statewide planning

- How research can provide support for program development

- Services Research

- Relevance, use and effectiveness of Evidence Based Practices (EBP�s)

- Assuring fidelity to EBPs

- Implementation infrastructure

- Epidemiology

- Explore New York�s support for basic science and discovery.

- Genetic studies

- Clinical trials

- Therapeutic markers

- Molecular biology

- Research with immediate relevance and application. Assess the focus and productivity of research to inform practice

Thank you for accepting your leadership responsibilities, and for initiating this timely and unprecedented review.

cc: OMH Leadership Team

Appendix B List of Assessment Visits

| Center - Program - Agency - Group | �Location | �Date� |

|---|---|---|

| Association for Community Living (ACL) | �NYCFO | �08/20/07� |

| Buffalo Psychiatric Center (BPC) w/MFH | �Buffalo, NY | �06/19/07� |

| Capital District Psychiatric Center (CDPC) | �Albany, NY | �07/02/07� |

| Coalition (Various Groups) | �90 Broad St. | �06/04/07� |

| Conference of Local Mental Hygiene Directors (CLMHD) | �Albany - 99 Pine St. | �08/23/07� |

| Cornell (Westchester Division) | �White Plains | �08/17/07� |

| Council of Behavorial Agencies | �Albany, NY | �06/13/07� |

| Creedmore Psychiatric Center (CPC)� | Queens Village, NY | �06/06/07� |

| Greater New York Hospital Association (GNYHA) | �555 West 57th St. | �06/25/07 |

| Health and Mental Health (ICL; The Bridge; FEGS; UIBH) | �40 Rector Street | �06/22/07� |

| Hutchings Psychiatric Center (HPC) w/MFH | �Syracuse, NY | � 06/20/07� |

| Hutchings Psychiatric Center (HPC) | �Syracuse, NY | �06/28/07� |

| Kingsboro Psychiatric Center (KPC) | �Brooklyn, NY | �06/06/07� |

| Kingsboro Psychiatric Center (KPC) | �Brooklyn, NY | �06/14/07� |

| Kirby Forensic Psychiatric Center (KFPC) | �Wards Island, NY | �05/25/07� |

| Mental Health Association (MHA/NYS) | �Albany, NY | � 09/11/07� |

| National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, Inc. (NAMI Metro or NYC) | �Fischman Law Office� | 08/16/07� |

| National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, Inc. (NAMI NYS) | �Albany, NY | �09/11/07� |

| Nathan Kline Institute (NKI) | �Orangeburg, NY | �07/07/07� |

| NY Association of Psychiatric Rehabilitation Services (NYAPRS)� | Albany, NY | �08/22/07� |

| Pilgrim Psychiatric Center (PPC) | �West Brentwood, NY | �06/05/07� |

| Pilgrim Psychiatric Center (PPC) | �West Brentwood, NY | �06/08/07� |

| Rochester Psychiatric Center | �Rochester, NY | �09/05/07� |

| Rockland Psychiatric Center (RPC) | �Orangeburg, NY | �06/01/07� |

| Saint Lawrence Psychiatric Center (St. Lawrence PC) | �Ogdensburg, NY | �08/28/07� |

| Second Chance (Cornell - Westchester Division) | �White Plains | �08/29/07� |

| Sing Sing Correctional Facility | �Ossining, NY | � 07/05/07� |

| South Beach Psychiatric Center (SBPC) | �Brooklyn, NY | �09/06/07� |

| Supportive Housing Network of New York (SHNNY) | �NYCFO | �06/15/07� |

| Western NY Children's Psychiatric Center (WNYCPC) w/MFH | �West Seneca, NY | �06/18/07� |

Appendix C Report of the OMH/OASAS Task Force on Co-Occurring Disorders:

Background and Opening Phase Recommendations

September 2007

Background

To better meet the needs of individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders and their families, the Commissioners of the New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH) and the New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS) announced the creation of a statewide Task Force on Co-Occurring Disorders on June 13, 2007. The Task Force - composed of consumers, families, broad representation from mental health and chemical dependency organizations, -and staff from OMH and OASAS - has been co-chaired by Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, of OMH and Frank McCorry, PhD, of OASAS.

The Task Force, based on its charge from Commissioners Hogan and Carpenter-Palumbo, unequivocally supports three commitments made by their State agencies:

- A commitment to identify and address limitations and barriers that people with co-occurring mental and chemical dependency disorders, and their families, experience when seeking care in the OMH and OASAS service systems in NYS.

- A commitment to recovery-oriented care that is consumer driven, based on hope and delivered with dignity, that recognizes the critical role of family and other relationships in a person�s life, and recognizes that the ability to be gainfully employed and contribute to one�s community are essential to quality of life and to self-regard.

- A commitment to culturally and linguistically competent care in light of the great diversity of the population of NYS and the recognition that care cannot be successfully provided unless it is provided with these competencies.

Why focus on improving services for people with co-occurring disorders?

In any given year, 2.5 million adults in the nation have a co-occurring serious mental illness and substance abuse disorder (NSDUH, 2004). Between 40-60 percent of individuals presenting in mental health settings have a co-occurring substance abuse diagnosis and 6080 percent of individuals presenting in a substance abuse facility have a co-occurring mental health disorder (Mueser, et al. 2006). The Table below depicts the 2003 rate of co-occurring disorders for individuals served in the OMH and OASAS systems. Because OMH and OASAS programs have not been required to report or record more than one diagnosis per individual, the rates identified in the Table are presumed to reflect a significant under-count. Importantly, this Table also does not reflect the number of individuals with co-occurring disorders who are not seen in either service system - which we presume to be significant.

According to Robert Drake, MD, PhD, the consequences of co-occurring disorders, particularly when untreated or poorly treated, are severe. They include: increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, pulmonary disease, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis and other medical conditions; high cost of healthcare due to high inpatient use and inability to adhere to treatment; loss of $100 billion in productivity; increased risk of suicide; crime victimization; homelessness; incarceration; and juvenile delinquency.

Treatment-Based Prevalence Rates of Individuals with Co-occurring Disorders in New York State

| For Recipients Seen in the Mental Health System During One Week in 2003 | For Admissions to the Substance Abuse System During the Year 2003** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Number | Number with SA Diagnosis or Disability | Rate | Total Number | Number With Mental Illness | Rate | |

| Total* | 171,363 | 30,714 | .18 | 209,365 | 62,953 | .30 |

| Inpatient | 14,076 | 3,814 | .27 | 40,842 | 16,487 | .40 |

| Residential | 24,165 | 8,140 | .34 | 20,669 | 4,680 | .22 |

| Emergency | 3,916 | 1,021 | .26 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Outpatient | 115,142 | 17,631 | .15 | 131,281 | 37,316 | .28 |

| Community Support | 48,722 | 12,333 | .25 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Methadone Maintenance | N/A | N/A | N/A | 16,573 | 4,470 | .27 |

* Because of overlap among programs, the total is less than the sum of program classes.

** OASAS Client Data System, April 2006

The benefits of treating both disorders are also well documented. Integrated treatment has been found to be more effective than non-integrated care (McHugo et. al, 1999); it has been shown to improve substance use outcomes with the majority of patients receiving integrated care achieving abstinence or substantially reducing harm from substance abuse. Most individuals experience improvements in independent living, control of symptoms, competitive employment, social contacts with non-substance users, and overall expression of life satisfaction (Drake 2006). Unfortunately, Dr. Drake has also stressed that 50 percent of individuals with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance use disorders receive no care; 45 percent receive poor care; and only five percent receive evidence-based care, a disturbing state of affairs.

The Work of the COD Task Force

Representatives from varied constituencies and geographies from throughout NYS were invited to participate in this time-limited and focused Task Force. In addition, experts in the field of co-occurring disorders treatment and evaluation were invited to serve as resources to the Task Force by attending the group�s meetings and being available for consultation. They include Robert Drake, MD, PhD, and Mark McGovern, PhD, of Dartmouth Medical School; Stan Sacks, PhD, and Richard Rosenthal, MD, of the Co-Occurring Center of Excellence; and Mary Jane Alexander, PhD, of the Nathan Kline Institute.

At its first meeting on June 29, the Task Force was charged by Commissioners Hogan and Carpenter-Palumbo with considering the current ambulatory system of care within OMH and OASAS and then providing the Commissioners, in September, a set of meaningful, measurable and actionable recommendations that can be implemented in a timely manner to improve the care of people with co-occurring disorders. At the first (of three) meeting of the Task Force, Dr. McGovern delivered a presentation on "Assessing the Capacity of Treatment Services for Persons with Co-Occurring Disorders". Consequent discussion at this meeting led to the formation of two workgroups, one clinical and one infrastructure, to each offer a limited number of recommendations for review at the second Task Force meeting. The following list of "Clients and families can …" goals or principles statements for both OMH and OASAS was established at the first meeting to help ensure that the Task Force and workgroup discussions remained faithful to their charge of putting clients and families first. Our common goal is that:

Clients and families can …

- Access care anywhere in OMH and OASAS-licensed programs;

- Receive one evaluation;

- Learn if they have a co-occurring disorder;

- Learn about treatment options;

- Collaborate in establishing a single treatment plan;

- Receive evidence or consensus-based treatment (or referral); and

- Participate in recovery-oriented care.

These client-focused goals served as a touchstone for the Task Force, and we hope will do so hereafter. They will provide a measure by which to examine all action steps to determine if they indeed serve the needs of recipients of care.